Lesson Goal: To understand how to read music like a musician, not like a robot…

Table of Contents

Prerequisites

Basic knowledge of music notation, the willingness to study, and the LOVE of music.

back to… Table of Contents

The Problem with How to Read Music is Taught

Alas, what most teachers “teach” and what most students “learn” about how to read music isn’t about reading music at all…. but is just the painful attempt to turn dots and symbols into digital sequences on a keyboard–completely devoid of musical understanding and typically no better than an English-only speaker trying to phonetically recite a poem in Hungarian.

Benefits of Learning How to Read Music

Before we start talking about HOW to read music, we need to ask: WHY should you learn to read music?…

And the answer is utterly simple…

Learn to read music

so you can read to learn music!

Those who learn to read music–in other words, those who become musically literate–will be richly rewarded by…

- Gaining access to an incredibly rich library of composed music.

- Being able to learn from countless educational materials.

- Deepening their understanding of how music works.

- Understanding how to think like a composer.

- Automatically learning how to “memorize” like a musician.

- Automatically learning how to improvise.

- Automatically being able to transpose music like a musician (not like a computer)!

Not knowing how to read music–in other words, being musically illiterate–is not something to be proud of. Knowing how to read music is not just a valuable skill in itself; the process of learning how to read–done right–teaches you how music works!

back to… Table of Contents

The Un-Musical Way to Read Music

Warning: Learning how to read music is not the way that most students are taught how to read music!

Unfortunately, most students start and end their musical lives by being taught the abstract, left-brain subject of music notation… without ever experiencing the concrete right-brain reality of making music.

A Typical Piano Lesson on How to Read Music

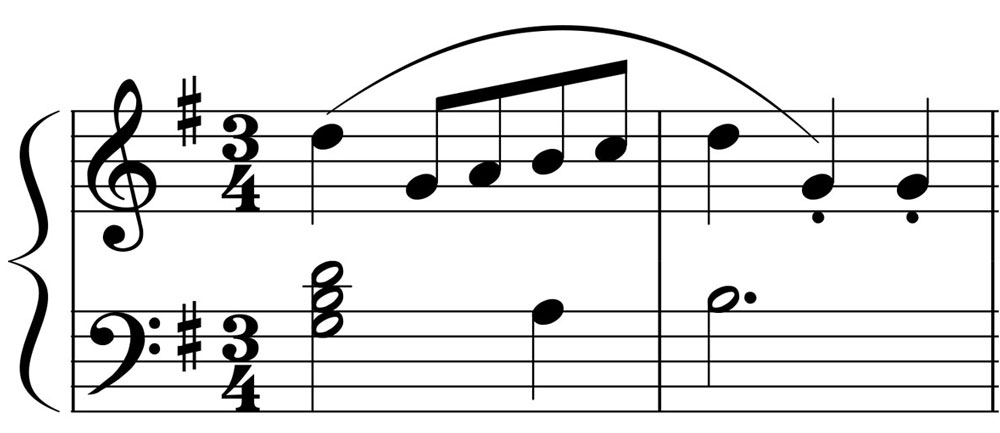

Teacher puts the following music in front of us and asks us to play…

Being an eager and trusting student who doesn’t know any better, I do the following–because it’s how I was taught since I was a puppy:

“Hmmmm. Let’s see (eyes fixed firmly on the first and topmost dot). The first note is… wait… start with the bottom line on the treble staff and say Every Good Boy Does Fine… Every (point at first line) – Good (point at second line) – Boy (point at third line) – Does (point at fourth line). Yes! D… That’s it! But which D? Hmmmm?! Let’s see… Middle C is down here (as I point to the imaginary line below the treble staff) called middle C, so that’s makes this the D above the C that’s above middle C, so I take my eye off the music and fix them on middle C of the keyboard that I know so well, then I count up an octave C to the next C plus one step is D. D! Got it! Ok. Now that I have that one, the next note is… Argh!!!”

It should be crystal clear that you never, ever want to read music like this… even as a beginner!

There are at least ten serious problems with this approach:

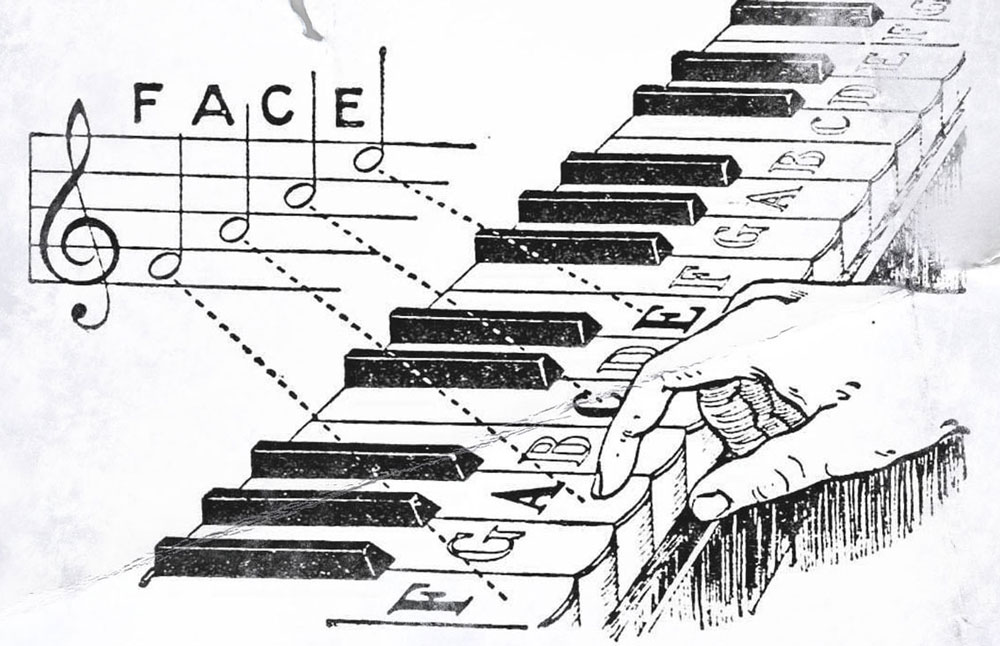

- You should never use a crutch like “Every Good Boy Does Fine” or “F-A-C-E” to learn where the notes are. If you rely on these crutches, you will never learn to walk on your own.

- It is ridiculous to read music “one-note-at-a-time”. This is the equivalent of trying to read English “one-letter-at-a-time”.

- Naming things and counting things consumes an enormous amount of your limited brain capacity that is better spent on more important things like looking for meaningful patterns.

- Reading music this way is mentally exhausting, leaving you no time and energy to focus on the important musical things like phrasing, articulation, dynamics, and interpretation.

- While you’re overwhelmed “reading”, you’re not listening. This is the valley of death for any musician.

- While it’s possible to become very skilled at translating music symbols into correct answers on a test, it’s possible to do so without any musical understanding whatsoever.

- Learning and performing music this way is like “reading” and reciting a foreign language phonetically or like painting by number.

- Trying to read music this way makes you dependent on brute force memorization.

- Reading music this way guarantees a performance that is robotic, uninspired, and uninspiring.

- Trying to read music this way, no matter how conscientious you are, will leave you feeling frustrated, defeated, stupid, and untalented.

But don’t despair… There’s a better way!

back to… Table of Contents

The Musical Way to Read Music

Lessons in how to read music like a real musician, not like a computer decoding a bunch of meaningless dots on a page!

Hint: Before fussing over the details, an expert music reader understands each symbol as just one part of a larger musical picture. In other words, an expert music reader zooms out before zooming in!

How a Musician Reads Bach’s Minuet in G

Using the first four bars of Bach’s immortal Minuet in G as an example, let’s take a look at all the ways we can understand what makes this piece tick before we play the first note…

Overall Impressions

The piece of music looks like classical music. It does not even remotely look like jazz or rock or ragtime or country.

The melodic-looking bass line suggests the use of something called counterpoint, a commonly used device in baroque music.

Meter

A quick inspection of the time signature tells us that this piece has an essential “three-ness” to it. And so, any artistic rendition will be infused with this lilting sense of “three-ness”…

Tonality & Key Center

The key signature (one sharp), along with a melody that strongly outlines a G Major scale tell us that this piece is in the key of G Major…

Of course, you should always confirm your theoretical analysis by ear. Play, listen, and sing the melody out loud and notice that these four bars have a definite major-ish quality that revolves around the note G!

Melodic Phrases

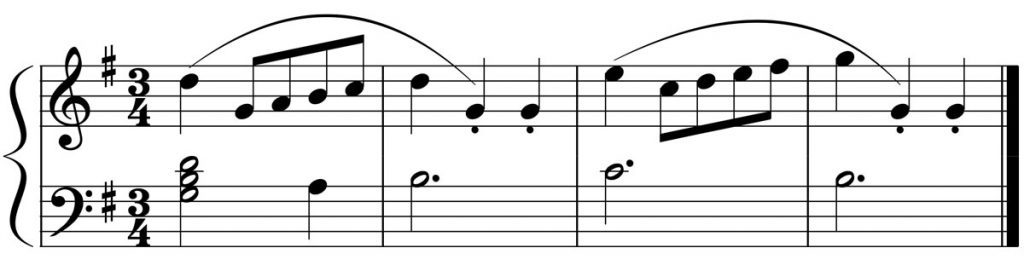

Judging by both the contour and rhythm of the melody, these four measures are sub-divided into two similar 2-bar phrases. They are so similar, in fact that they may be more aptly called phrase A1 and phrase A2…

Melodic Shape

Notice the well-defined contour in the melody that has the very same shape in each 2-bar section. You might conceive of it as a doodle of arrows!

Rhythmic Motives

Notice the simply, catchy, well-defined rhythmic motive that is repeated identically in each 2 bar phrase…

Harmonic Structure

The chord progression is shown below along with the Roman Numeral Analysis and all chord tones circled:

The I chord establishes the key center G and major-ness of the piece, while the IV chord in bar 3 creates harmonic tension that is released when the I chord returns in bar 4.

Notice how many chord tones are in the melody and how many melody tones are in the harmony. You will see this time and time again in every kind of music!

Detailed Melodic Analysis

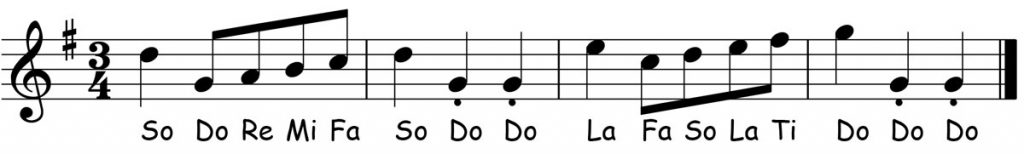

Here is the melody analyzed in functional terms using Solfege. Sing the melody out loud and be receptive to the unique sound-feelings of each Solfege syllable with respect to the key center Do and with respect to each other…

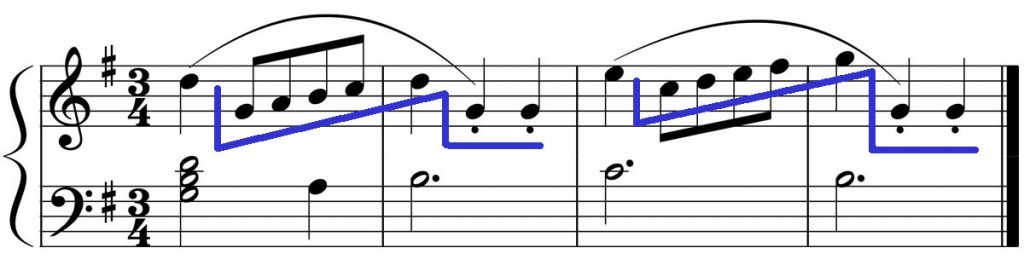

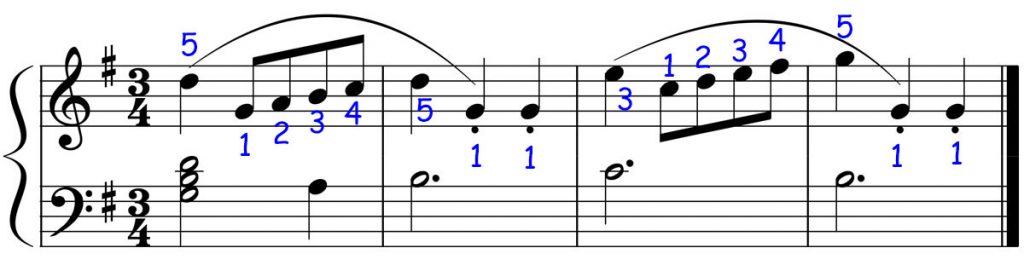

Fingering

The expert sees a fingering for this passage that makes physical, mental, and musical sense. It should be easy to play and consistent with the flow of the phrases. One solution is shown below. Notice the logical five note groupings with pinkies on the highest note in each phrase and thumbs on the lowest note in each phrase:

Putting it all Together

For now, notice how the meter, phrasing, rhythm, melody, and harmony all work together to define what makes this piece of music really tick!

Don’t freak out. You are not expected to be able to do all the above at this point. The intent, for now, is to expose you to the depth of musical understanding that’s possible and to give you a sense direction as your musicianship develops. All this will happen very quickly if you study and practice the right things (form, meter, rhythm, scales, chords, and chord progressions) the right way… Promise!

back to… Table of Contents

The Takeaway

Learning how to read music like a musician requires you to embrace a fundamental truth about how music works…

MUSIC is a LANGUAGE!

(Music is NOT math)

Consider the Letter M…

The letter M is one of twenty-six arbitrary symbols in the English alphabet. By itself, M has no intrinsic meaning. The letter M contributes to meaning only when put into some larger context–as part of the word Music, for example.

Likewise, consider the note F#…

F# is one of many arbitrary letters in the music alphabet; it has no intrinsic musical meaning. F# contributes to meaning only when put into some larger context–as part of the D Major Scale (D-E-F#-G-A-B-C#-D), for example. As part of that D major scale, F# is the very note that makes that scale sound major.

Just as letters are combined into words, phrases, and sentences in an upward spiral of meaning… musical notes are combined into phrases and forms in an upward spiral of musical meaning.

And so, your expertise in music reading grows by studying musically-useful patterns… scales, chords, chord voicings, progressions, form, meter, characteristic stylistic devices, and so on.

In summary, knowing your ABCs is not enough if you want to write poetry. In fact, knowing your ABCs is not enough if you just want to recite someone else’s poetry well. The same is true when it comes to reading and performing music.

Expert Music Readers…

… read music like you are reading these words–in meaningful chunks called words, phrases, and sentences.

… do not have some super human ability for processing huge strings of meaningless, unrelated information.

… have lots of experience reading, hearing, and playing meaningful musical patterns.

… do not read music one-note-at-a-time any more than you are reading these words one-letter-at-a-time.

Expert music-reading is no more a talent than learning to read English.

back to… Table of Contents

Discover more from PIANO-OLOGY

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.